A HISTORY OF SUNBEAM

In the beginning there was Alderman John Marston, JP. John Marston was apprenticed to the Jeddo Works of Wolverhampton as a japanner (metal lacquerer). In 1859, at the age of 23, he bought two existing tinplate manufacturers and set up on his own.

Marston, an avid cyclist, built his first bicycle  in 1887. According to legend, when Marston’s wife, Ellen, saw the first bicycle she remarked on how the black enamelled frame reflected the sun. Thus the Sunbeam name was born. Fact, or just a nice story? Nobody knows.

in 1887. According to legend, when Marston’s wife, Ellen, saw the first bicycle she remarked on how the black enamelled frame reflected the sun. Thus the Sunbeam name was born. Fact, or just a nice story? Nobody knows.

Sunbeam bicycles were the finest money could buy with a price tag to match. Notable Sunbeam owners included Edward Elgar.

The Marston companies were prosperous and in 1899 his right hand man, Thomas Cureton, persuaded him to venture into the manufacture of motorcars. Henry Dinsdale was poached from the Wearwell Cycle Company to build a prototype.

A number of cars were built between 1899 and 1901, but no attempt was made to market them. Maxwell Maberly-Smith designed the first Sunbeam to reach production. This cycle-car, called the Sunbeam-Mabley (Sunbeam misspelled the unfortunate Mr Maberly-Smith’s name) was arguably the least conventional Sunbeam ever. Its wheels formed a diamond pattern, supposedly rendering it skid-proof. Whether this feature has ever been tested, history does not confirm.

The Sunbeam-Mabley went on sale in 1901 for 130 pounds. Approximately 130 cars were built which was respectable for the turn of the century. Despite its unconventional design, it was reasonably successful.

Sunbeam realized that for serious production, a more conventional design would be necessary. T.C. Pullinger was appointed as works manager in 1902. Under Pullinger, Sunbeam began marketing French Berliets as their own. Badge engineering is by no means a recent invention.

The Berliet-based Sunbeam 12/16 was produced between 1903-1904 and established Sunbeam as a serious manufacturer. Two six-cylinder Sunbeams were produced in 1904, but production centred on the four. A new engine and gearbox were introduced in 1905 and the car became the 12/14.

In 1905, the Sunbeam Motorcar Company Ltd was formed as a separate entity from John Marston Ltd. Pullinger left to join Humber. Angus Shaw, previously Pullinger’s chief draftsman, was appointed chief designer and his products established Sunbeam’s enviable reputation for quality. However, Sunbeam were about to acquire a new designer who would make the company one of the greats.

Louis Coatalen was born in Brittany in 1879. In France, he worked for Panhard, Clement and De Dion Bouton. On arriving in England, he worked (purely coincidentally) for Humber and Hillman before joining Sunbeam in 1909.

Coatalen set to work designing many new models, such as the12/16, which is widely regarded as being one of the best cars of the era. By 1911, Sunbeam were building 650 cars per year, while the factory covered 4.5 acres.

Coatalen soon turned his attention to racing cars, many of which he drove himself. His first, the Nautilus was a pencil-nosed device. While experimenting with Nautilus, he discovered that it ran better if the wheels were balanced. Coatalen was also the first to put the oil pump in the sump and was an early proponent of shock absorbers.

Nautilus was replaced by Toodles II which was much more successful.

Four Sunbeams were entered for the French Grand Prix and Coupe De L’Auto in June 1912. The cars came 1st, 2nd and 3rd in the Coupe De L’Auto and 3rd, 4th and 5th in the Grand Prix. Sunbeam instantly became internationally famous.

By 1913, Peugeot were dominating racing although a Sunbeam finished 4th at Indianapolis. That year Sunbeam also began to participate in record-breaking.

Coatalen “acquired” a Peugeot and studied it closely before designing new cars for 1914. His friend Dario Resta brought the Peugeot to England to show it throughout the country. In Wolverhampton, Resta inadvertantly left the Peugeot somewhere convenient for it to be taken to Coatalen’s house. There it was stripped overnight with every significant part being measured and sketched. By morning it had been reassembled. Kenelm Lee Guiness (as in KLG spark plugs) won the 1914 Tourist Trophy in one of the Peugeot-inspired Sunbeams.

Motor racing was about to take a backseat, however. With Europe on the brink of war, Sunbeam’s efforts were to be directed elsewhere.

In 1914, Europe plunged headlong into war. In addition to motorcars and  motorcycles, Sunbeam had built up a thriving aero engine business. The war created a sudden demand for aero engines. Many were fitted to seaplanes and Bristol fighters.

motorcycles, Sunbeam had built up a thriving aero engine business. The war created a sudden demand for aero engines. Many were fitted to seaplanes and Bristol fighters.

Sunbeam cars also played a part in the war. The 12/16 and 16/20 were used as staff cars and ambulances, not only by Britain, but also by the Australian Army. To free up factory space for the aero engines, production of the 12/16 was transferred to the Rover works. Some say that the Rover-built cars not as good as the Wolverhampton models.

Arguably, the greatest moment for Sunbeam in the air came later, in 1919. The airship R34 made the first aerial crossing from the UK to the USA and back in 183 hours. This feat was not to be repeated until 1928, when Germany’s Graf Zeppelin made a double crossing. R34 was powered by five Sunbeam Maori DOHC V12 engines. Many other components for the R34 were also made in the Sunbeam works.

Early in 1918, the Marstons were rocked by the death of their third son, Roland, at the age of 45. On March 8th, the day after Roland’s funeral, John Marston died. Ellen died a few days later.

Sunbeam were in a strong financial position after the war. They had also gained invaluable technical experience which put them in good stead for the years to come. Sunbeam production recommenced in 1919 with the 16hp (based on the pre-war 12/16) and the 24hp (from the pre-war 25/30).

On Friday, the 13th of August 1920, Sunbeam merged with the French company Darracq. Alexandre Darracq built his first car in 1896. One Darracq, known as Genevieve, became the world’s most famous veteran car when it starred in the film of the same name. (To be precise, Genevieve was actually two Darracqs, having been built from the remains of two cars.) Alfa Romeo and Opel started out in the car industry by building Darracqs under licence.

After M. Darracq retired, the firm was taken over by British interests. In 1919, Darracq bought the London-based firm of Clement-Talbot. Clement-Talbot was founded in 1903 for the import, and later licence production, of French Clements.

The new company was named STD Motors Ltd. The group also included the commercial vehicle producer W & G Du Cros, the spring makers Jonas Woodhead and the equipment and dynamometer makers Heenan & Froude.

With the combined resources of the STD group, Coatalen returned to motor racing. STD racing cars were variously badged as Sunbeams, Talbots and Darracqs depending on marketing requirements.

The designer Ernest Henry is said to have joined Sunbeam around this time, coming from Ballot. Henry had previously worked for Peugeot on the cars that had influenced the 1914 Sunbeams. I’ve received some fiery correspondence on the subject of Henry which has left me in doubt as to the level of his direct involvement with Sunbeam. Some argue he was fully employed by Sunbeam, others argue that he merely acted as a consultant. Whatever the case may be, the racing cars produced at the time Henry is supposed to have worked for the firm did not produce the hoped for results.

In 1922, overhead cam sports variants of the Sunbeam 16 and 24 were introduced. Another addition to the catalogue was a smaller model, the 14.

After Henry, Bertarione and Becchis were poached from Fiat. This move seems to have paid off because in 1923, Major Henry Segrave won the French GP for Sunbeam. Sunbeams also took second and fourth places. It was the first time a British car and driver had won a European Grand Prix and Sunbeam and Segrave were idolised by enthusiasts throughout the Empire.

Sunbeam followed this up with a win in the 1923 Spanish GP with Divo at the wheel. For 1924 the cars were supercharged but failed to finish in France. Segrave made up for it by winning in Spain that year.

For 1924, Sunbeam made some changes to its range of models. The four cylinder Sunbeam 14/40 replaced the 14. A new six, the 20/60, was introduced and was highly regarded by the press of the day. Other new models were the 12/30 and the six cylinder 16/50.

In 1924, Sunbeam quietly announced the Sunbeam 3-Litre Super Sports. It went on sale in 1925 and was one of the most advanced cars of its day. It was based on the chassis of the Sunbeam 16/50, but under the bonnet was Britain’s first production twin overhead camshaft engine.

The Sunbeam Super Sports was capable of “over 90 mph”. The speedometer could only read up to 90, so it was unclear precisely what it was capable of. The engine developed 85-90 bhp at 3800-4000 rpm (130 bhp in supercharged form). Cycle mudguards were fitted to the brake back plates so that they turned with the wheels. The engine used dry sump lubrication, a system said to have been invented by Sunbeam.

A Sunbeam Super Sports was entered for Le Mans in 1925 where it finished second. Louis Coatalen must have been pleased at trouncing the Bentleys. Messrs Coatalen and Bentley had been involved in an argument over the link between road car and racing car design. Coatalen said that racing car and road car design were interrelated, while Bentley argued that there was no connection between the two.

Also for 1925, the Sunbeam 24 (or 24/70 as it was now known) was dropped from the catalogue. The Sunbeam 16/50 meanwhile was renamed the Talbot 18/55.

Sunbeam set their first World Land Speed Record in 1922 at Brooklands with  Kenelm Lee Guiness at the wheel. He drove a 350hp V12 Sunbeam which is still on display at Britain’s National Motor Museum. KLG averaged 133.75 mph over two runs.

Kenelm Lee Guiness at the wheel. He drove a 350hp V12 Sunbeam which is still on display at Britain’s National Motor Museum. KLG averaged 133.75 mph over two runs.

In 1924, Malcolm Campbell took over the Sunbeam with the intention of raising the record to 150 mph. He made many changes to the car and christened it Bluebird, a name which was to be used on all of the Campbell family’s record breakers. At Pendine Sands he set the record at 146.16 mph. Campbell had failed to meet his target and was not satisfied. He tried again in 1925 and managed 150.87 mph.

A new V12 Sunbeam was built for Henry Segrave in 1925/6. Initially it was called the Ladybird, but was later renamed Sunbeam Tiger. In 1926 Segrave pushed the record up to 152.33 mph at Southport.

In 1990, the Tiger made another attempt on its old record and hit 159 mph which was not bad for a 65 year old car.

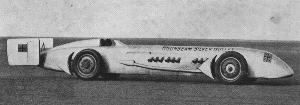

Sunbeam made its last successful attempt on the record in 1927 with the 1000 hp Sunbeam powered by twin V12 engines. Segrave made 203.79 mph at Daytona. This car is also on display at the National Motor Museum.

Financial troubles were looming. It was decided in 1926 that Sunbeam would concentrate on luxury cars and control of the STD racing department was transferred to Talbot-Darracq in France.

In the mid-twenties, record-breaking made Sunbeam a household name. Had you asked any schoolboy in the Empire which car he dreamed of owning, chances are it would be Sunbeam or Bentley. Today Sunbeam would draw a blank. How times change.

In 1926, Sunbeam launched the 30 and 35 hp models. This was the largest chassis Sunbeam ever built with 5 litre (30hp) or 5.5 litre (35hp) straight eights. Saloon, limousine and tourer bodies were available. It lasted until 1930.

Also new for 1926 were the new 16hp and 20hp models. The 20/60, meanwhile, was replaced by the 25hp. The 14/40 was dropped in 1927 and never replaced.

By now Sunbeam were in deep financial trouble. The firm was never paid for some World War I aero engine work and it had overstretched itself in motor racing. Coatalen had borrowed heavily to finance the racing programme and the firm could not pay it back.

Sunbeam made one final attempt on the Land Speed Record in 1930 with The Silver Bullet, built for Kaye Don. Despite it dramatic appearance and supercharged twin V12s totalling 48000cc, it was a disaster and achieved nothing.

Silver Bullet, built for Kaye Don. Despite it dramatic appearance and supercharged twin V12s totalling 48000cc, it was a disaster and achieved nothing.

The 3 Litre Super Sports was axed in 1930. A new sports model called the Speed Twenty was launched in 1933, but unfortunately it was competing in-house with the Talbot 105.

Sunbeam’s final fling came with the Dawn of 1934. It was an attempt to move downmarket. Unfortunately it was too well made and advanced to be competitively priced.

STD Motors went into receivership in 1934. Talbot of London was the only healthy component of STD at this time. In January 1935, Clement-Talbot Ltd was sold to the Rootes Group. Despite Talbot being a profitable concern, Rootes set about phasing out the old Roesch-designed models and replacing them with Hillman- and Humber-based Talbots. This horrified enthusiasts, but the Roesch cars did not fit in with Rootes’ plans of being a mass producer.

With Talbot of London sold off, the Receivers had to find buyers for the rest of STD. A deal was struck with William Lyons of SS Cars to buy Sunbeam in 1935. Lyons needed a new name for his cars because of the Nazi connotations of SS. By purchasing Sunbeam he would be acquiring instant heritage and prestige.

In 1931 Sunbeam had branched into the production of trolleybuses (a cross between a bus and a tram). Rootes purchased the trolleybus business in 1934. Sunbeam Commercial Vehicles was subsequently sold by Rootes and purchased by Guy in 1949. With Guy it became a part of the British Leyland combine.

Since the formation of STD Motors, the group had been phasing out the Darracq name and badging the French cars as Talbots instead. Depending on marketing requirements, they were sold as Talbots, Talbot-Darracqs or Darracqs in different territories.

Talbot of Suresnes, France was purchased by Anthony Lago who had worked for STD for many years. French Talbots and Darracqs built under M. Lago are popularly known as “Lago-Talbots” or “Talbot-Lagos”. Although now an independent company, the story does not end here. We shall be hearing more of Talbot of Suresnes.

Just as it looked like everything was settled, Rootes stepped in and snapped up Sunbeam Motor Cars from under Lyons’ nose. Lyons was somewhat annoyed, to put it mildly. He went on to invent his own marque and build its heritage from scratch. He made quite a good job of it too, as the Jaguar name today is vastly better known than Sunbeam.

Rootes assigned Sunbeam the task of building luxury cars for the group. The old Sunbeams were axed and work started on the new Sunbeam 30. It used a Georges Roesch-designed straight-eight engine in a stretched Humber chassis. The Rootes brothers decided to take the prototype on a continental holiday. Unfortunately, before they reached the channel the chassis broke! In any case the market at that time was not right for such a car. The prototypes were broken up and the project abandoned.

There was no room for Sunbeam alongside the existing Rootes Group range of Hillmans, Humbers and Talbots. With that, Rootes consigned Sunbeam to history.

Rootes discovered that it had a problem. The Rootes Group Talbots, built in London, were being confused with Lago’s Talbots (nee Darracqs), built in Suresnes.

Rootes also had a valuable marketing device in the form of the defunct Sunbeam marque. The solution was to create a new marque: Sunbeam-Talbot. From 1938, the existing British Talbots were rebadged as Sunbeam-Talbots. This is why the Sunbeams that followed used a Talbot badge and grille rather than the traditional Sunbeam badge and grille.

The entry-level Sunbeam-Talbot was the Ten. This model was launched in August 1938 and was an upgrade of the previous Talbot Ten. The chassis had its origins in that used in the Hillman Aero Minx. The engine was an 1185cc sidevalve Minx unit with an alloy head. They were available with four-door saloon, drophead coupe and sports tourer bodywork.

Next model up was the 2 Litre. Launched in 1939, it was based on the Ten but used the 1944cc sidevalve engine from the Hillman 14 and Humber Hawk. Very few of these were built during 1939 because of the advent of war. Like the Ten, they were available as saloons, drophead coupes and tourers.

The 3 Litre was simply a rebadged Talbot 3 Litre. It was based on the Humber Snipe, using that car’s chassis and 3181cc sidevalve six with alloy head. The body styles were saloon, sports saloon, drophead coupe and sports tourer.

The 4 Litre was another new model for 1939. This one was based on the Humber Super Snipe. It used the same chassis as the 3 Litre/Snipe with a 4086cc sidevalve six and alloy head. Body styles were as for the 3 Litre with the addition of touring saloon and touring limousine.

War intervened again in 1939. All Sunbeam-Talbot production was suspended for the duration of the war. Rootes continued to build Minxes and Snipes for military use, but there was no need for sporting Sunbeam-Talbots.

Rootes did not only provide cars for the war. Rootes provided Britain with 14% of its bombers, 60% of its armoured cars, 35% of its scout cars, 50000 aero engines, 300000 bombs, etc, etc. Rootes were given a new factory at Ryton-on-Dunsmore to handle all of this and William Rootes was knighted for his efforts.

When production resumed again in 1945, only the 10 and 2 Litre were continued. The 3 and 4 Litre were never revived. In 1946, production was transferred from the ex-Talbot London plant to the new Ryton plant.

In later years, the London plant would become studios for Thames Television. Many of your favourite (!) TV shows would have been made in the old Talbot factory.

The new post-war Sunbeam-Talbots were launched in 1948. Built at Ryton, they carried over the chassis from the 2 Litre with running gear drawn from the Rootes parts bin. Two models were available. The 80 was fitted with an overhead valve version of the engine from the old 10. The 90, meanwhile, had an OHV derivative of the engine from the 2 Litre.

They were available with saloon bodywork from British Light Steel Pressings or drophead coupe bodywork by Thrupp & Maberly.

Under Rootes, Sunbeam-Talbots continued the tradition of STD by competing in motorsport. Now, however, they concentrated on rallying rather than racing. The pre-war types were used in rallies with some success. It was, however, the 90 which proved itself to be an effective rally weapon.

It would take more space than I have here to document the 90’s rallying history.  The success of the Rootes Sunbeam-Talbots surprised many people, considering their more humble origins compared with their STD forebears. Arguably the model’s greatest moment came when a Mk III won the 1955 Monte Carlo Rally outright.

The success of the Rootes Sunbeam-Talbots surprised many people, considering their more humble origins compared with their STD forebears. Arguably the model’s greatest moment came when a Mk III won the 1955 Monte Carlo Rally outright.

In 1950 the Sunbeam-Talbot range was facelifted. The 80 was dropped from the range and the 90 was upgraded to become the Mk II. It received a new chassis with independent front suspension. The OHV engine was increased to 2267cc. Externally, the headlamps were raised by three inches to enable the car to meet American regulations. The front driving lamps were replaced by a pair of small air intake grilles.

The 90 Mk IIA was introduced in 1952. It received various tweaks to the specification as a result of Rootes’ rally experience. Externally, the only change was the deletion of the rear wheel spats.

The final incarnation of the car appeared in 1954. This model was known simply as the Sunbeam Mk III. The Talbot part of the name was dropped because of continuing confusion with the French Talbot concern. In fact many earlier Sunbeam-Talbots were sold in continental Europe as Sunbeams for this reason.

The Mk III had larger front air intake grilles and three portholes along the sides. Underneath there were few changes, although by now the engine was developing 80 bhp, way up from the 64 bhp of the Mk I 90.

Production of the Mk III ceased in 1957.

George Hartwell was a Rootes dealer in Bournemouth and a friend of the Rootes family. Hartwell specialised in tuning Sunbeam-Talbots and campaigned them in rallies. He began cutting down Sunbeam-Talbot drophead coupes into two-seat roadsters and calling them Hartwell Coupes.

Rootes were sufficiently impressed with the car that they decided to produce their own version. The design was refined by Raymond Loewy’s studios. The new sports model was christened the Sunbeam Alpine in honour of the success of the Sunbeam-Talbot team in the Alpine rally. The Talbot part of the name was left out for the benefit of continental motorists, to whom Talbots were French grand tourers, rather than British roadsters.

The Alpine was launched in 1953 and ran to 1955, receiving an upgrade in 1955 in line with the saloon and DHC models.

The Alpine was also a successful rally car and such greats as Stirling Moss and Peter Collins campaigned them for the works team. Stirling Moss and Sheila van Damm tested a specially prepared Alpine at Jabbeke in Belgium, each exceeding 120 mph (193 kph).

In 1955, a new smaller Sunbeam was launched. The Rapier was the 2-door variant of Rootes’ new Audax range. The 4-door variants were launched in 1956 as the Hillman Minx and Singer Gazelle. The Series I Rapier used Rootes’ new 1390cc OHV 4 cylinder engine.

Like its forebears, the Rapier was immediately pressed into service as a rally car. In time, it would become one of the most popular rally cars of the period.

The Series I Rapier continued in production until 1958. By this time the Sunbeam Mk III had been dropped from the catalogue. In 1958 the Series II Rapier was introduced. The engine size was increased to 1494cc while the twin Zenith carburettors were carried over from the late Series I models.

Externally, the most obvious change was the introduction of the Rapier’s tail fins. The Series II also received a traditional Talbot grille. A convertible Rapier became available for the first time.

In 1959 the Rapier was again upgraded. The most significant mechanical changes for the Series III were an alloy cylinder head and front disc brakes. Cosmetically, there was new chrome trim and a wooden veneer dashboard.

Also for 1959, the Alpine name was revived on a new sports car. It combined the short wheelbase floorpan of the Hillman Husky, the running gear of the Rapier III, and a body styled by Kenneth Howes. The new Alpine was assembled for Rootes by Armstrong Siddeley.

On the other side of the channel, Automobiles Talbot (nee Darracq) was absorbed by Simca in 1959 and production ceased. Although this has no bearing on the Rootes Group, it will become significant later on.

For 1960, the Series II Alpine was introduced. The engine was upgraded to 1592cc. The only obvious external difference was the introduction of a window channel to the leading edge of the doors.

In 1961 the Rapier was upgraded to the same specification as the Series II Alpine and became known as the Series IIIA. The IIIA had no external changes.

The Alpine and Rapier were updated again in 1963. Carrozzeria Touring of Milan, who assembled Alpines and Super Minxes for the Italian market, presented Rootes with a proposal for a facelifted Alpine. The fins were cropped short and the boot redesigned with twin fuel tanks in the wings. Rootes liked the new boot layout, but retained the original fins for the Series III. The hardtop and windscreen were also redesigned. Mechanically, there were no significant changes, although midway through the model’s life the Zenith carburettors were replaced with a Solex.

Alpines were now available as either “Sports” or “GT” models. The GT came with a hardtop as standard, but the hood was deleted to make the interior more roomy. The GT came in a softer state of tune for comfort rather than performance.

Originally, the Series IV Rapier was to be the car which emerged as the Humber Sceptre. At the last minute, Rootes decided to continue the old Rapier alongside. The Rapier received a heavy facelift for 1963. There was a lowered bonnet line with a new grille, new chrome trim down the sides and 13 inch road wheels. Underneath was an all-synchromesh gearbox, while the engine now produced 78.5 bhp. The convertible was dropped from the range.

In 1963, Touring introduced their own unique Sunbeam. The Venezia was based around the Super Minx/Vogue/Sceptre range. It used Superleggera construction meaning alloy panels mounted on a tubular framework. It used Sceptre running gear. Few were made and most were left hand drive.

In England, coachbuilders Thomas Harrington & Company were also building their own Sunbeams. These were Alpines converted into GTs with the addition of a fibreglass roof. Very few were built and many were tuned by Hartwell.

For 1964, Rootes finally introduced the cropped fins for the Alpine IV. The grille was also changed and an automatic transmission (shudder!) became an option. Mechanically, there were still no significant changes.

Ian Garrad, manager of Rootes’ operations on the West Coast of the USA, had been watching with interest the success of the AC Cobra. The Cobra was the result of fitting a Ford V8 into the AC Ace. In 1963, Carroll Shelby and Ken Miles were each commissioned to build a prototype Ford V8-powered Alpine.

The Shelby prototype was eventually presented to Lord Rootes who was sufficiently impressed to give the project the go ahead. The Mk I Tiger, introduced in 1964, combined the Series IV Alpine bodyshell with a 4.2 litre Ford V8 engine. The Tiger was assembled by Jensen in West Bromwich. It was dubbed Tiger in honour of the 1920’s Sunbeam racing car of the same name. In some markets, however, it was sold as the Alpine V8.

In addition to spawning this image boosting model, the Alpine had provided a means for Sunbeam’s return to motor racing. Rapiers had been competing in touring car racing with some success and the Alpine was pressed into sports car racing.

The racing Alpines are probably best known for their assaults on Le Mans. 1961 saw Sunbeam return to the French circuit for the first time since the 1920’s. One car was disqualified, but the other finished 16th overall, averaging 90.9 mph and winning the Index of Thermal Efficiency trophy.

In 1962, an Alpine finished 15th, averaging 93.24 mph. 1963 would, perhaps, best be forgotten with both cars failing to finish. For 1964, Tigers were entered. Again both cars failed to finish, although blame for this is sometimes attributed to the standard of engine preparation by Carroll Shelby.

The Tiger was also used successfully in rallying.

By the early 1960s Rootes were finding themselves increasingly in deeper financial trouble. There had been teething problems with the Imp, the two medium car ranges (Minx and Super Minx families) were proving to be a drain on resources and industrial relations problems were bringing production to a standstill.

Rootes found themselves with no option than to seek a merger with another company. Talks with Leyland came to nothing. In 1964, a deal was made with Chrysler. Chrysler bought 30% of the voting shares and 50% of the non-voting shares in the company.

In 1965 the Alpine and Rapier received the new five bearing 1725cc engine and thereby became the Series V models. There were few other changes.

For 1966 there was a new small Sunbeam. The Imp Sport was, as its name suggests a performance derivative of the Hillman Imp. It received twin carburettors, extractors, a brake servo, reworked head and camshaft, etc, etc along with more upmarket interior trim. The Imp Sport and the 998cc Sunbeam Rallye Imp displaced the Tiger as Rootes’ main rally weapon in the late 1960s.

The Imp Sport was followed in 1967 by a fastback derivative, the Stiletto. The Stiletto used the Hillman Imp Californian/Singer Chamois Coupe bodyshell combined with the Imp Sport motor.

Rootes also had plans for an Imp-based sports car called the Asp which would have tackled the Spitfire, Sprite and Midget. The Asp was a very attractive car, resembling a scaled-down, but modernised Alpine. Unfortunately Chrysler killed the project.

In 1967, Chrysler took full control of Rootes. Ironically, in 1963 Chrysler had also taken control of Simca in France who in turn controlled Automobiles Talbot. Chrysler had unwittingly reunited Sunbeam, Talbot and Darracq.

The updated Tiger II with a 4.7 litre Ford V8 was launched in 1967. Unfortunately it was to be short lived. Chrysler did not like the idea of one of its products using a Ford engine so the car was scrapped. Plans for an all new Tiger with a Chrysler V8 came to nothing.

1967 saw the introduction of a new Rapier. Styled by Royden Axe, it was based on Rootes’ new Arrow range (Hunter and derivatives). It had the five bearing 1725cc engine with twin Stromberg carburettors and an alloy head.

A performance derivative called the H120 was introduced for 1968. This one had been tuned by Holbay, gaining an improved head, camshaft and Weber carburettors.

The Imp Sport received a facelift in 1968 in line with the rest of the Imp range.

Also in 1968, the Alpine was finally laid to rest. A new Alpine appeared in 1969. This one was another `Arrow’ Rapier derivative, this time slotting into the range below the Rapier.

In 1970 the Rootes Group was renamed Chrysler UK. Singer, purchased by Rootes in 1955, was laid to rest. The existing models were all dropped with the exception of the Vogue (by now another Hunter variant). The Vogue was renamed “Sunbeam Vogue” for 1970, but lasted for only six months.

Production of all Sunbeams shifted to the Linwood plant in Scotland in 1970.

The Imp Sport was renamed “Sunbeam Sport” for 1970, a model which also replaced the Singer Chamois Sport. The only changes were cosmetic, most notably twin headlights as per the Stiletto.

Rootes had always concentrated on building cars of a higher quality than their competitors and charging a little more. Chrysler set about on a cost cutting exercise. Unfortunately the customers did not like this. They also began to phase out the old Rootes marque identities in favour of the Chrysler identity. Not only was this harmful to customer loyalty, but it created an uproar within the workforce. Chrysler seemed to be heading for a fall.

The Stiletto was dropped in 1972. The Alpine was replaced in 1975 by a five door Simca-based hatchback called the Chrysler Alpine, also styled by Roy Axe.

Production of all Sunbeams and Humbers ceased in 1976 and by 1978 the Hillman name had been phased out in favour of Chrysler.

Use of the Sunbeam name did not end there however. For many years, Rootes and its successor Chrysler had been using the Sunbeam name on various Hillmans, Humbers, Singers and Chryslers built for export. Virtually every late sixties/early seventies Rootes/Chrysler UK product was sold somewhere in the world with Sunbeam badges.

Thus there were Sunbeam Minxes, (non-Sport) Imps, Gazelles, Vogues, Chamois, Sceptres, Avengers, Hunters and even Sunbeam-badged Commer vans.

Back in Britain, things were not looking good for Chrysler UK. In order to fund new model development they were forced to seek help from the British Government and the Chrysler Corporation. One of the results of this funding was Project 424, the Imp replacement.

Chrysler managed to get the car onto the market after only 18 months development. To speed up development and keep costs to a minimum, the new model was heavily based on the Avenger. Consequently when it appeared in 1977, it turned out to be much larger than the Imp.

It was available in only one body style, a three door hatchback. Engines were the 1300cc and 1600cc Avenger units and the Imp unit enlarged to 930cc. Chrysler, like Rootes, realised the folly of not taking advantage of the heritage behind the Sunbeam name. However corporate policy dictated that the old marque names be phased out in favour of the Chrysler identity. Hence the new British baby car became the “Chrysler Sunbeam”.

Virtually every Rootes Group Sunbeam was a sporting version of an existing Hillman or Humber (the exception being the 1970 Sunbeam Vogue, in effect a luxury Hillman Hunter). The Chrysler Sunbeam marked a complete turnaround, in that it was intended solely as basic transport. But not for long.

In 1978 Peugeot bought Chrysler Europe. Peugeot wanted a new name for all their ex-Chrysler products. A search through their archives came up with such suggestions as Bugatti, Delage, Delahaye and Sunbeam. The rights to the Bugatti name have of course since been passed on to new owners.

In the end it was decided to revive the Talbot name since the English and the French both claimed it as their own. Thus the range of cars came to be known as Talbots, Talbot Simcas, Talbot Sunbeams and Talbot Matras – Matra being Simca’s sports car division. In addition, the newly acquired Formula 1 team became Talbot Ligier.

For 1979, the Talbot Sunbeam hatchback gained two new derivatives. The 1600 Ti used the Avenger Tiger engine to create a hot hatch with loud go-faster stripes, spoilers and garish paintwork. The much more subtle, but demonically fast Sunbeam Lotus gained a 2.2 litre Lotus engine. A simple two tone finish made it one of the ultimate Q-cars, able to accelerate to 60 mph in 6.6 seconds.

The Sunbeam Lotus became Talbot’s new rally weapon, winning the World Rally Championship in 1981. The rally version could accelerate to 60 mph in 5 seconds.

In 1981 the Linwood plant in Scotland, home to all Sunbeams since 1970, was closed and with it production of the Talbot Sunbeam ceased. This time it really was the end. The Sunbeam name was never again revived.

As for the rest of the revived Talbot concern, the British commercial vehicle division (nee Commer, Karrier and Dodge UK) and the Matra specialist car division were sold to Renault. Matra’s Espace people mover went on to be a huge success for Renault. Funds for the Ligier Formula 1 team ran out and plans for sister Peugeot and Citroen teams never eventuated. Ligier went elsewhere for backing.

The Talbot passenger car division, starved of new models, continued to lose money. The new Talbot Arizona for 1985 was renamed Peugeot 309 at the last minute. By the end of the 1980s, the only Talbot model was the Express van, made in conjunction with Peugeot, Citroen and Fiat. The Talbot name is no longer used.

When Talbot production ended, Ryton switched over to building Peugeots. Peugeot production at Ryton continued until the factory was finally closed in 2006.

With thanks to Ian Walker, Roly Forss and John Pinkerton for their help in finding errors in my work.

Very comprehensive.

Very readable history. One of the best on the internet.

Mike